Defensible Architecture and Asset Management for Electric Utility Cybersecurity #

Webinar #

Recorded on February 22, 2024

Presenters #

- Markus Mueller, Dragos, Inc.

- Jason Shea, Southern California Edison

Presentation

Summary #

Utilities frequently rely on reference architectures when attempting to build a defensible network as part of a robust cybersecurity program. Some examples of the best practices that typically follow from these references include:

- Define and segment the layers

- Defense at each layer

- Traffic inspection and filtering between layers

- Encrypt critical data

- Deploy security solution on the network and endpoints

- Zero Trust

While utilities can be quite successful with these reference architectures and best practices, an intelligence driven approach—figuring out the problems you have, and then addressing those problems—can guide utilities to maintain a strong cybersecurity program even as the business grows and changes. It can also help guide utilities to make smarter investments that yield real risk reduction.

In the context of OT systems, intelligence-driven defensible architecture is based on five considerations:

- Process understanding: Process understanding involves identifying and understanding the critical systems, learning how they operate, and what happens when they fail. The Crown Jewel Analysis is an approach to help organizations with this process of figuring out which assets are the most critical and their possible attack vectors.

- Threat scenarios: Organizations need to determine what threats exist and the threat scenarios that are likely to impact their environment; threats and threat scenarios can vary based on size, location, and purpose of the organization.

- Operational constraints: Operational constraints help determine what defensive actions and architecture can be designed and implemented to maintain operations without hindrance.

- Business constraints: Like operational constraints, business constraints help determine the policies and processes that are available to build a robust cybersecurity program.

- Capabilities: For a deployed strategy to be effective, the organization must have the capabilities available to digest and respond to the data provided by the defense mechanism.

The remainder of this section looks at a fictitious water utility, ACME Co, to help illustrate the above process in practice at varying operational scales.

Small Utility #

ACME is a relatively small water utility serving 6,000 customers. They have seven wells, two large water tanks, four small water tanks, one treatment plant, and two lift stations. For business systems, they use cloud-based software (e.g., Microsoft 365 or a cloud-based customer information system), and for OT systems, they use Rockwell programmable logic controllers (PLCs), Ignition, and a Badger Meter system.

In this fabricated example, an ACME employee fell prey to a phishing email, resulting in downloaded malware. The malware infected a handful of computers and two OT systems: the metering system and the employee workstation. ACME lost revenue due to being unable to bill customers, and the company lost programming and files due to poorly maintained backups. This incident acted as a catalyst for ACME to implement intelligence-driven defense.

ACME started by reexamining their processes. A Crown Jewel Analysis identified that Well 1, Tank 1, and the singular water treatment plant were most critical to operations and meeting demand. As ACME is not a large target, nor one of exceptional importance, they determined that the most likely threat scenario to defend against is opportunistic ransomware. However, limited staff, a limited budget, and infrequent production outages constrained their response. With these considerations in mind, ACME implemented several new defense measures.

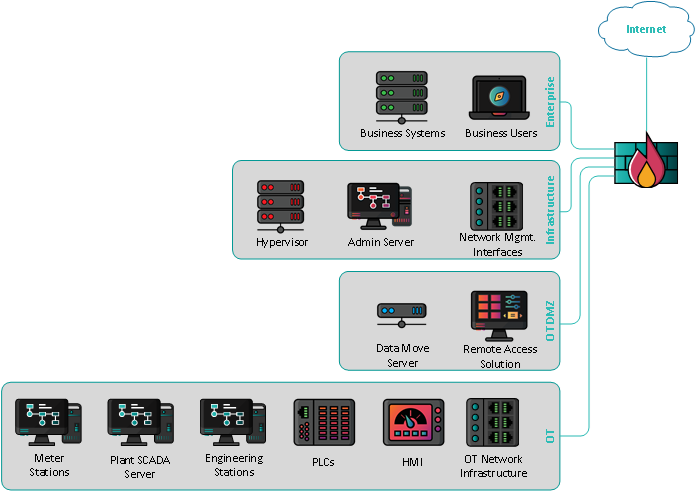

Resource constraints meant ACME could not implement a separate domain network for their OT infrastructure, so they used a shared infrastructure model. Using only the one firewall, ACME segmented the network with different firewall rules and different zones on the firewall for the IT and OT networks. They also established an OT DMZ to monitor and control data movement between the IT and OT systems and focused on making sure data moved through the DMZ. Figure 7 below models this hypothetical segmentation scenario.

Figure 7. ACME Network Segmentation

In addition to network segmentation, ACME rolled out new security controls, including partnering with engineers and operators to create and maintain an asset inventory and hardening system security with a password vault and role-based user access with a few defined roles (Admin, Operator, and Read Only). With the ransomware threat in mind, they focused on backups and deployed a system to manage PLCs and maintain their backups, and they expanded backup solutions for OT with a local network attached storage (NAS) and offline removeable disks. With shared infrastructure, ACME recognized the potential for an attacker to pivot from IT to OT too easily, so they required multi-factor authentication (MFA) on remote and admin accounts. Although these defense mechanisms enhance overall security at ACME, they do not inherently enable a defensible architecture.

To be defensible, ACME developed policies and processes to complement these technology defense measures. As such, they created security use cases and began centralized logging of events on a security incident and event management (SIEM) system. Rather than creating alerts for every possible concerning event in the logs, they focused on events to which they knew they could and would respond. They built playbooks to define the actions they would take in a ransomware incident such as IT/OT disconnection and OT restoration during an event. They joined intelligence networks like the WaterISAC and cross-trained their IT and OT employees to better equip and prepare them for future events. Incident response tabletop exercises and restoration tests highlighted some gaps, which ACME addressed to validate their newly implemented intelligence-driven defense architecture.

Medium Utility #

ACME has acquired an electric utility that serves a similar customer base and scaled up to a medium utility. As a medium-sized water and electric utility, ACME’s infrastructure and technology stack has grown to include additional infrastructure and new IT and OT systems, namely a new water SCADA system and an electric distribution management system (DMS). ACME repeated the Crown Jewel Analysis and found that the SCADA system and DMS were their most critical systems. Having expanded in size as a utility, ACME may now be a larger target, thus increasing their threat scenarios to not only opportunistic ransomware but also targeted ransomware and hacktivism. Their constraints remain the same: limited budget, limited staff, and infrequent production outages.

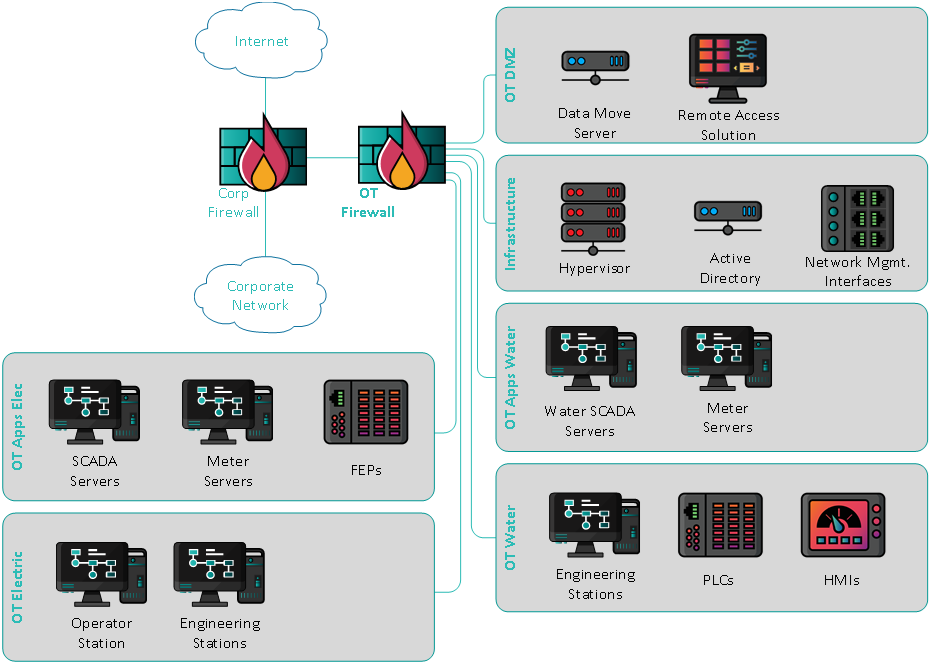

In response to growing threats, ACME bolstered their network segmentation with dedicated OT infrastructure and internal segmentation by function/process, grouping together components that supported the same process. This strategy also helps address vulnerabilities in legacy systems that may not have modern security capabilities by putting defenses close to the systems. Similarly, it helps to isolate vendor devices that may not be trusted by enabling the utility to segment that device and the traffic to and from it. In general, ACME restricted data flow to the one up/one down model—data flows that traverse security zones only flow one zone higher or one zone lower. Figure 8 depicts this level of segmentation.

Figure 8. Increased ACME Network Segmentation (Water and Electric)

Figure 8. Increased ACME Network Segmentation (Water and Electric)

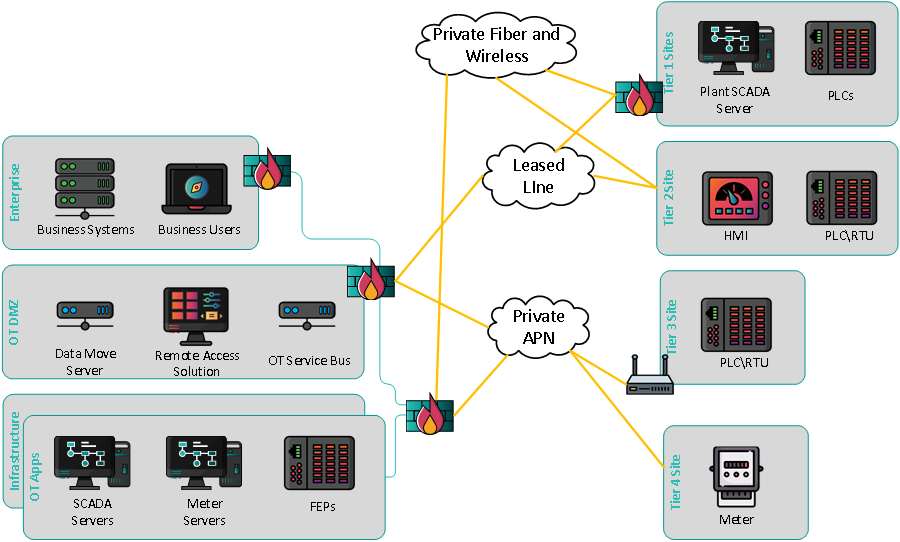

ACME also reviewed their field area network (FAN) and made plans to address identified threats. As a small utility, ACME was able to use public communication infrastructure without worry. However, intel indicated that hacktivists in the geopolitical space were targeting publicly available IP addresses. They moved to private communication paths like private cellular, deployed some of their own network, and stopped using public infrastructure (i.e., with public IP addresses) as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. ACME Field Area Network

Figure 9. ACME Field Area Network

ACME also strengthened their identity management practices while trying to limit the number of passwords each user must use. They maintained segmentation between IT and OT, so users typically had an identity for the enterprise networks (managed with Azure AD), a method for remote access, and access credentials to assets in the production environment. They further hardened the system by implementing application whitelisting/allowlisting, EDR, and a privileged access management (PAM) solution. They continued to focus on recovery and augmented their backup strategy with local/site-to-site replication and offline-to-tape solutions to ensure that if there was an attack, they could recover quickly and completely.

With changes in defense mechanisms also came changes in actions and capabilities to maintain defensibility. ACME increased ICS network visibility with an industrial visibility platform in their Control Center. They conducted hunts into their own environment to actively look for signs of malicious activity based on industry intel, and they developed more use cases and playbooks, such as how to respond to compromised credentials or a compromised system and how to perform forensic triage. ACME expanded its intelligence network by joining the Electricity Information Security and Analysis Center (E-ISAC) and elevated their security operations center (SOC) by hiring a managed security service provider (MSSP). ACME continued to run tabletop exercises and site recovery drills. They even made site recovery a part of the commissioning process for new equipment. Engineering and security would collaborate to ensure that recovery processes were functioning.

Large Utility #

In a final example, ACME expanded operation by adding utility scale solar and wind generation, a large battery energy storage system (BESS), and allowing customers to install solar and BESS behind the meter, particularly solar and wind. To manage these new systems and requirements, ACME deployed an advanced distribution management system (ADMS), AMI metering, and their own cellular network in some locations. The Crown Jewel Analysis identified the ADMS and water SCADA system as most indispensable. Ransomware remained a threat, but they also worried about advanced persistent threats (APTs) that might be targeting electric utilities. Given ACME’s larger size, they now face heightened levels of scrutiny and oversight from regulators, further constraining operations.

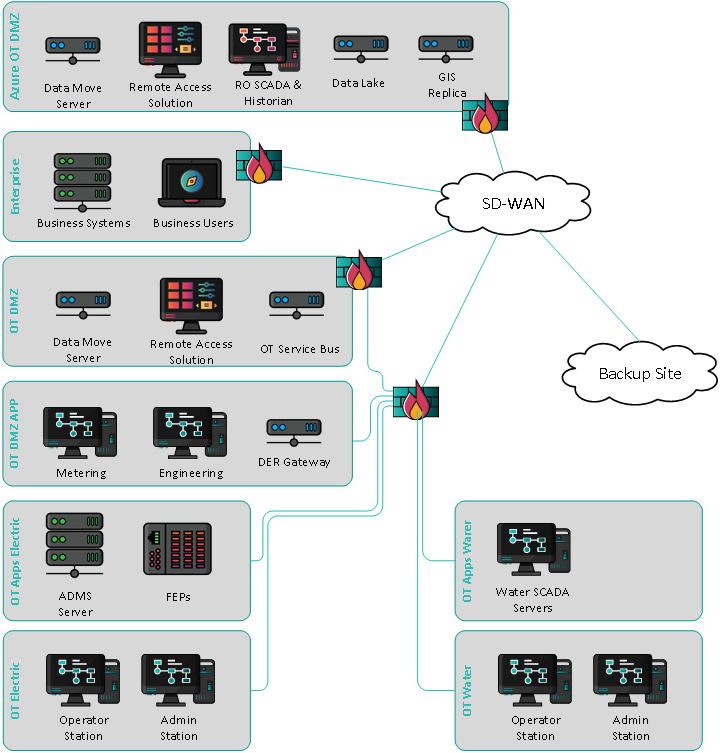

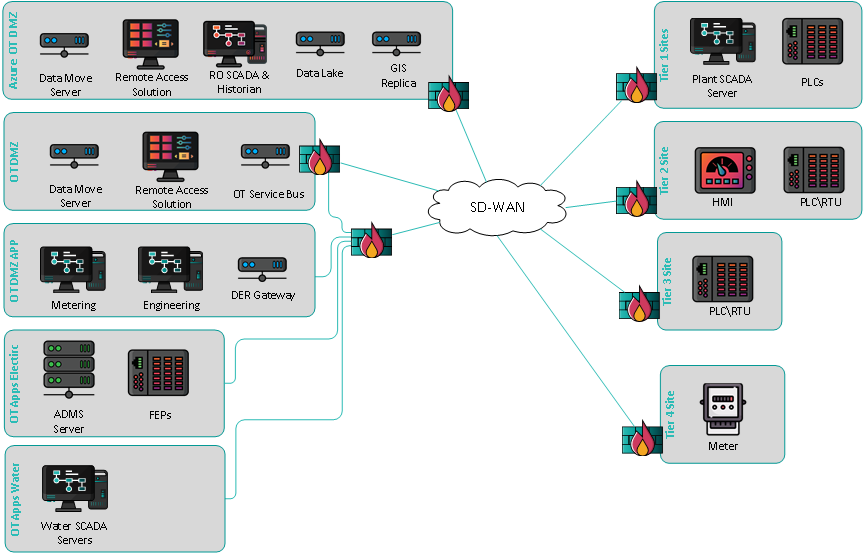

To adapt to their changing environment, ACME maximized network segmentation. They thought about site and path resilience and deploying technologies like software defined networking (SDN) in an SD-WAN (software-defined wide area network) to enable multipath communication to primary and backup sites. They implemented micro segmentation and containers to expand asset protection. Figure 10 below depicts their new level of network segmentation.

Figure 10. ACME Network Segmentation (Water, Electric, and Generation)

Figure 10. ACME Network Segmentation (Water, Electric, and Generation)

With distributed energy systems and behind-the-meter generation like customer-sited solar, ACME knew they were not going to be able to control both sides of the connection for grid-connected devices. This required security enhancements to their FAN and shifting to an SD-WAN model where all endpoints had access rules, and traffic was controlled across their network. Figure 11 models this new field area network.

Figure 11. ACME Field Area Network (Water, Electric, and Generation)

Figure 11. ACME Field Area Network (Water, Electric, and Generation)

ACME further enhanced their identity management capabilities to increase usability given the additional personnel. They sought to make access to read-only accounts in the OT DMZ a little easier by implementing an Azure AD for the OT DMZ which connected to the distinct Enterprise Azure AD via Azure’s B2B settings. They kept the separate credentials for OT assets but made the management more flexible so they could more tightly control who had access to what equipment.

ACME reviewed and enhanced most of their security controls as part of scaling up their defensible architecture. They codified an asset management and a change management program, started baseline tracking, and implemented a risk-based vulnerability management program to prioritize and optimize security actions. ACME did not let these enhancements detract from their continued focus on maintaining backup solutions that enable them to withstand a security event, including local/cloud replication, immutable cloud storage, and standby systems.

Just as before, ACME’s architecture defensibility is enabled by their monitoring and response capabilities. As such, ACME expanded visibility within the ICS network and added more logging—both OT system logging and ICS device logging—and created more specific and niche playbooks, like insider threats and defensible cyber stance to instruct operation during an attack. Having more experience and knowledge under their belt, ACME began contributing to information sharing groups rather than solely receiving intel. Their workforce advanced and was able to create an in-house L2+ SOC and dedicate responders to security events. Lastly, to prepare for a catastrophic event, ACME rounded out their tabletop exercises and recovery drills by running tabletop exercises that included the executives and leadership and developing and practicing a system-wide recovery drill.

Lessons Learned #

As seen in each of the three scenarios above, ACME followed the same steps each time. They looked at and understood their industrial processes, identified threats faced and constraints imposed, and developed capabilities that enabled a defensible architecture. Intelligence-driven defensible architecture is a deceivingly complex process. It requires intimate knowledge of how operations and the business function to design an intelligence-driven strategy that fits the environment. However, a strategy is only as successful as its weakest link.

Deployed technologies and processes must support event detection and response, in addition to being robust, to protect critical assets from a spectrum of threats. Although working towards a zero-breach architecture might be ideal, it is not realistic, and utilities need to focus on establishing procedures that define how to maintain operations during an attack and how to recover quickly and fully following an attack. Playbooks can be particularly helpful for utilities to document exactly how they will respond (i.e., what actions they will take) to a specific type of event. Some organizations may even decide that preparing redundant equipment (e.g., a pallet of the required assets) to be delivered in response to an event is necessary to stand up a new, clean network to restore operations. Collaboration and community within industry is imperative to help investor-owned utilities, cooperatives, and municipalities alike adapt to the ever-increasing level of grid interconnectedness and vulnerability.

While broad intel to understand likely threats and scenarios (e.g., opportunistic ransomware vs. an APT), is instrumental to strategic decisions around building a defensible architecture, bringing the latest intelligence streams into the cybersecurity program is typical of a mature program and less essential early on. Utilities may see some benefit from spending a small amount of time (e.g., one person-hour per week) reviewing streams to be aware of trends and drive conversations with OT staff to understand potential exposure. For example, the CyberAvengers attacks in the fall of 2023 targeted PLCs made by a specific manufacturer. Companies around the world had these PLCs installed and available on the public internet. Following intel feeds would have alerted a company to double check with their engineering whether they have these PLCs in production environments.

Many organizations have opportunities to target what is coming in the door rather than having to be reactive to what is available for procurement. Organizations can hold vendors accountable for the security of their products by pushing for secure-by-design practices. Additionally, organizations can ask themselves how they will operate without that product or service. Playbooks can document the actions the utility would take if the product or service becomes unavailable.

Additional Resources #

- Scott Fitch and Michael Muckin, Defendable Architectures: Achieving Cybersecurity by Designing for Intelligence Driven Defense (2019)

- SANS, The Five ICS Cybersecurity Critical Controls (November 2022)

- Dragos, Operational Technology - Cyber Emergency Readiness Team (OT-CERT)

- E-ISAC

- WaterISAC