Best Practices for Secure Remote Access and Cloud Security in the Electricity Sector #

Webinar #

Recorded on February 8, 2024

Presenter #

- Justin Searle, InGuardians

Presentation

“Defensible architectures and remote access have to go together”

—Justin Searle, InGuardians

Summary #

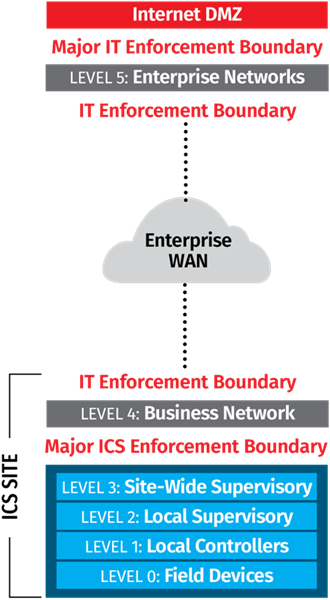

Remote access—being able to access critical control systems from outside the physical facility, from an external network—has become an essential business requirement for many organizations. But remote access brings significant cybersecurity risks just as it makes operations more flexible. A popular, recent resource from the SANS Institute, “The Five ICS Cybersecurity Critical Controls,” identifies “Secure Remote Access” and “Defensible Architecture” as two of the five critical controls. Moreover, a “Defensible Architecture” is a prerequisite for the “Secure Remote Access” control, as shown in Figure X below. These two critical controls stand out as paramount to provide secure remote access and cloud security, which are necessary capabilities to mitigate supply chain cybersecurity risks.

Flowchart of the 5 Critical Controls from SANS

Flowchart of the 5 Critical Controls from SANS

A Defensible Architecture #

Network security organization is enhanced by structuring networks into defined security zones. The Purdue Model1 is a linguistic tool commonly used to talk about the delineation between security zones, rather than to guide which security checks and balances to put in place. Each level in the Purdue model has different components, services, and functions, and a single level can contain multiple subnets. Security zones typically represent a grouping of networked assets that serve a single service or function. These security zones become the defensible areas, where security administrators can apply monitoring and controls to track and/or limit traffic or users.

An enforcement boundary naturally fits not only between Purdue levels but also between components, services, and functions in separate zones within a Purdue level, enabled by this segmentation into security zones. Firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and other network monitoring solutions are typical technology controls placed in the boundary, depending on budgets, risk levels, and other considerations.

One of the most important aspects of a defensible architecture is defining the demarcation between IT and OT systems (typically, between Purdue levels 4 and 3). This demarcation acts as the primary line of defense (i.e., the primary enforcement boundary) for the OT space. OT systems are heavily dependent on network defenses, external to what can be installed onto an OT device. Assets should be placed in either the IT or the OT environment, but not both nor on a dividing line. The placement is determined by considering whether the asset could have an impact on the OT processes. If there could be any potential disturbance in the OT process by an asset, it should be placed in the OT side of that demarcation.

Figure 5. Focus on enforcement boundaries between Levels 5 and 4. (Justin Searle)

Once the IT/OT boundary has been created and established, the next step is limiting what is allowed to come into the OT area. Using the Purdue model, as shown above, levels 4 and 5 are the business and enterprise networks, respectively. These are considered part of the IT environment and distinct from the OT environment, which comprises levels 0 – 3.

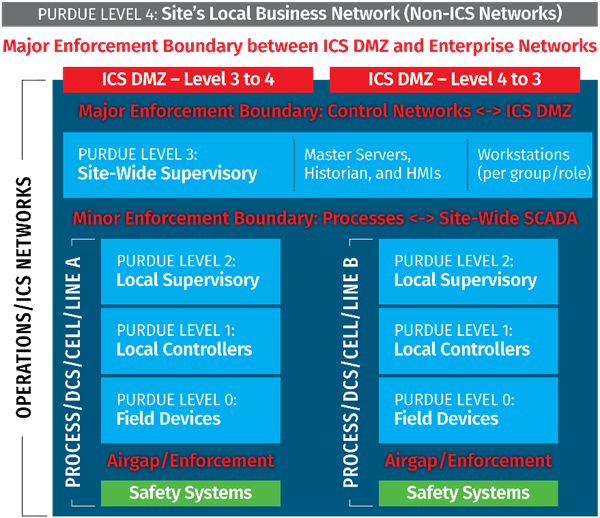

General cybersecurity guidelines dictate that no assets in level 3 or lower should have direct internet access. That is, internet and email should not go deeper than Level 4. In the OT environment, Active Directory (AD) may be useful for managing accounts and access to OT components, but this AD should be separate and distinct from the Enterprise AD used in the IT environment. Shared credentials between an Enterprise AD and an OT environment AD creates substantial risk that compromised credentials could be used to target operations. Another important aspect of this demarcation point is the inclusion of a demilitarized zone (DMZ) as part of a strong perimeter for the OT environment. The DMZ will include assets like servers that can facilitate the exchange of information between the IT and OT environments. This allows organizations to ensure the traffic between IT and OT environments can be inspected before transfer.

Small sites may use a single ICS DMZ, but larger sites with a complex amount of IT/OT traffic may scale or expand the number of DMZs to separate traffic and mitigate risk. Each of these DMZs can be segmented at this level such that if one of the servers or data transferring assets is compromised, the ability for the attacker to move laterally is harshly limited. Security services and patch managers should not be at this DMZ level, but rather in Purdue level 3.

One common example of multiple DMZ occurs with separate DMZs for the “northbound” and “southbound” network traffic. That is, assets in level 4/5 push data and information to the “southbound” DMZ and assets in Level 3 pull from it. Similarly, assets in Level 3 push data and information into the “northbound” DMZ and assets in Level 4/5 pull from there. In addition to IT/OT ICS traffic DMZs, there may also be DMZs for cloud access and remote access, further separating traffic and mitigating risk.

A common security mistake is sharing management solutions across both IT and OT across the boundary. For example, shared AD exposes OT credentials to attacks on Enterprise AD. Compromised Enterprise AD would then allow an attacker to completely bypass the IT/OT boundary. Shared network and virtualization management leads to IT/OT perimeter bypasses as well. Organizations should separate all management solutions between IT/OT, such as separate AD with no trust relationships and managing OT networks, virtualization, backups, patching, and endpoint detection and response (EDR) from within the OT environment, keeping all IT and OT tools separate entirely. It is possible to use the same solution within both IT and OT; however, different management servers should be used. This setup allows for bulk licensing and shared knowledge between the IT and OT teams. Moreover, it reduces the number of communication streams between the IT and OT environments that must be managed.

Figure 6. Focus on enforcement boundaries between Levels 4 and 3 and Levels 3 and 2. (Justin Searle)

Software Defined Networking (SDN) is becoming more common and is frequently found on wide area networks (WANs) to manage the network communication pathways. Different SDN solutions will have different capabilities, so care should be taken to understand the fit for purpose. For example, some SDN solutions may look like a management solution, in which case the earlier discussion on separating management solutions for IT and OT environments applies. If a single SDN solution has capabilities to manage assets within IT and OT at once, this could be a tool to upend protections that separate the IT and OT networks and offer a path for an attacker to reach operations.

The biggest limitation to modern end-point security or EDR solutions is where they can be installed in the OT environment. Assets that can run EDR solutions are typically in Purdue Level 3, because many of them are Windows and Linux servers. It is less common that devices in lower levels, closer to the operations, can support EDR. But in the context of security with a defensible architecture, an attacker will have to gain access to Level 3 devices first making them an ideal place for EDR. Many modern EDR solutions are cloud-backed to conduct deeper investigation of data, so organizations will likely have to determine whether the trade-off for more capabilities for a little bit more risk is worthwhile.

Enforcement boundaries should also exist between Purdue Level 3 and the subprocesses in levels 2, 1 and 0, as shown in Figure 6. Internal enforcement boundaries within the OT environment are critical to reduce the attack surface and prevent pivoting from one process to another, or even to the supervisory level. Safety systems and communication should be isolated from the rest of the ICS network.

Secure Remote Access #

Remote access into the OT environment will come from Level 4/5 or direct from the internet. It is recommended to have two separate steps for including remote access into an OT environment because having a single step remote access solution would create a single point of failure. The first step in the two-step remote access solution is reaching the ICS DMZ. This connection should leverage a VPN or a Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) remote access solution. There should be mandatory two-factor authentication. This first step of remote access can use either a separate, standalone authentication specifically for remote access or in some cases using Enterprise AD. Using a combination of separate, standalone authentication for contractors or consultants and Enterprise AD for internal users is also possible, but this is dependent on the organization. Many ZTA solutions allow the user to connect to AD, but it is up to the organization whether to do so. If you do make this connection, use the Enterprise AD rather than an OT AD.

The second step to remote access is then from the ICS DMZ to individual assets or a jump host in Level 3. This step acts as a second level of authentication to add security. This jump host should use the OT AD authentication method that is separate from the Enterprise AD, as discussed above. This step allows two separate sets of credentials and two layers of control. It also allows for fine control over access to specific assets. The first step lets the user access the perimeter of the ICS environment, but the second step can limit access to specific assets within the ICS environment.

Additional controls can bolster this 2-step process to support detection and response and recover capabilities. For example, organizations should record the remote access session in either step 1 or step 2 so that the security team can identify what the remote access user is doing. Creating a record of the session can be done in either step 1 or in step 2, but generally not in both. Organizations should also prevent remote access users from bringing in data unless they absolutely need to. There are exceptions, such as vendors bringing in a patch, but these exceptions depend on a case-by-case basis, so it must be explicitly stated who can bring in what. If a remote access user is bringing in any type of file or data, it is strongly recommended that these files or data are uploaded to a separate file server in an ICS DMZ or ZTA that can scan the file for vulnerabilities, as well as store the file, store the hash of the file, and keep a record of who brought it into the environment. After the checks are done on the file or data, it can then be facilitated through the DMZ to the appropriate location.

Cloud Connectivity #

Cloud connectivity should be considered very carefully. While it can add huge business and operational benefits, it also adds risk. Cloud connectivity should be treated like traditional vendor remote access, but with 24/7 access. The risks are quite similar between vendor remote access and cloud services, and in both cases, the security risk team should carefully consider them to determine if the benefits outweigh the risks and what appropriate measures should be taken to mitigate risks.

One example of a risk that utilities should consider is geopolitics. Organizations should ensure the cloud provider’s servers are not located in an “adversarial” country, which could come with additional risks. Another consideration for cloud solutions is the robustness of the solution. Solutions hosted by the three big vendors (Google, Amazon, and Microsoft) tend to be secure and robust, while other vendors may require additional scrutiny.

There are several best practices for risk mitigations in these scenarios. Organizations should use cloud services that support transport layer security (TLS) protected protocols or VPNs to protect data in transit so that all the data going to and from the cloud service will be encrypted. In general, firewalls on the perimeter of the ICS environment should have rules that are as specific as possible, specifying which machines from the cloud and which assets in the ICS environment are allowed to communicate via the DMZ; firewall rules should use internet protocol (IP) addresses, if possible, hostnames if not. Similarly, firewall rules should be highly specific in both directions—to and from the cloud.

Finally, all traffic should move through a DMZ specifically for this cloud connectivity. This traffic could flow through either a server that brokers traffic between cloud and ICS assets (some cloud services may supply just such an asset to install in the DMZ) or a web proxy with allowlists between specific systems and services. In either case, the solutions should support logging.

There may be cases where devices or agents internally need to communicate directly with the cloud. This case carries a little more risk, which may be mitigated by further limiting what locations those assets can communicate with (e.g., limit by IP address if possible, or hostnames if not). Organizations may also choose to build security perimeters around these internal assets as well to block pivoting and to address the scenario that the cloud service has been compromised.

One emerging use case for cloud services supporting the OT environment is to manage back-up for the OT environment. Like with other shared services, administrators for the OT environment should ensure that IT and OT environments use separate instances of that management solution. Cloud backup could be an acceptable solution if the organization has done their due diligence that it will be feasible. One consideration that may be pertinent to electric utilities is to ensure that the backup does not saturate network traffic such that SCADA communications could be affected.

Conclusion #

For electric utilities, many innovations—including DER, microgrids, smart cities, electric vehicles, and others—rely more heavily on communications between systems than legacy systems and could look more like remote access or cloud systems in terms of communication requirements. Electric sector organizations that have shied away from remote access may be forced into it through these new technologies. Moreover, the vendors of these new technologies may be requiring remote access more and more, so organizations should build perimeters around those assets.

Creating a defensible perimeter between IT and OT is paramount to enable remote access and cloud connectivity to ICS systems. Without this defensible perimeter, an attacker could leverage remote access to pivot from the IT network to the OT network and would therefore immediately be one step closer to potential impacts on operations. Enforcement boundaries within the OT environment between assets or systems bolster defense, especially for critical assets. Without these enforcement boundaries, an attacker could leverage remote access to a low value asset in the OT environment to pivot to a critical asset.

Similarly, if cloud connectivity is being utilized in one asset or process, this asset or process needs to be isolated from other assets and processes to limit and block pivoting, thus reducing attack surfaces. The key to remote access and cloud connectivity is having a defensible and secure network architecture.

Actions Toward Defensible Architecture and Secure Remote Access #

Defensible architecture #

- Segmentation between IT and OT (Purdue Levels 5 and 4)

- One or more DMZs as appropriate to separate traffic between IT and OT (within Level 4)

- Separate all processes (in Level 2) from the site-wide supervisory (Level 3)

- Segmentation between processes within OT environments

- Separate management services (e.g., AD) for IT and OT

Secure Remote Access / Cloud Access #

- Separate DMZs for remote access and cloud access as appropriate

- 2-step authentication for humans

Additional Resources #

- SANS, The Five ICS Cybersecurity Critical Controls (November 2022)

- ISA/IEC 62443 Standards – Security of Industrial Automation and Control Systems

- Williams, T. J. “The Purdue Enterprise Reference Architecture.” IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 12th Triennial World Congress of the International Federation of Automatic control. Volume 4 Applications II, Sydney, Australia, 18-23 July, 26, no. 2, Part 4 (July 1, 1993): 559–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-6670(17)48532-6.

-

Officially, the Purdue Enterprise Reference Architecture (PERA), but frequently referred to as the Purdue Model. ↩︎