Governance, Policies, and Procedures for Third-Party Cybersecurity Risk Management #

Webinar #

Recorded on March 21, 2024

Presenters #

- Terri Khalil, Ampyx Cyber (formerly Ampere Industrial Security)

- Roland Miller III, Cyber Florida

Presentation

Summary #

The rapid rise of digitalization in the electric utility industry has necessitated robust and strategic cybersecurity governance frameworks to address supply chain risk management. By examining current best practices on policies and procedures, reviewing typical models for managing cybersecurity, and discussing different approaches to communicate cyber risk, organizations will have a clear pathway to safeguarding information and maintaining operational and data integrity in today’s complex digital landscape. Governance policies and procedures are a necessary complement to the technology controls that are frequently thought of first when discussing cyber security.

When creating governance policies, an organization must build a governance function and set up a charter. An organization may be able to leverage existing governance models found in a code of business conduct, a corporate compliance committee, or a regulatory affairs team, among others, or start from scratch. During the formation process, there are three essential “tiers” to include: an officer-level executive/senior sponsorship committee, a director-level steering committee, and a working group consisting of subject matter experts from relevant areas, team leads, and managers. Then, in partnership with appropriate stakeholders, the newly formed committee must review and agree upon a charter that outlines the group’s mission, purpose, responsibilities, scope, and guidelines.

As with the creation of anything new, issues and obstacles are inevitable. One of the foundational pieces to governance is centralized procurement that enables third-party risk management. Without an existing method to identify and manage third-party engagements and enforce requirements and selection processes consistently, organizations will face major challenges to implementing new governance policies and managing risk. For example, an employee may make a purchase for a business service on their personal credit card and expense it to the company, or they may have a company card that allows them to make purchases without formal review. Upon purchasing, however, the employee may have unknowingly agreed to inappropriate or unmanaged regulated data sharing and third-party retention of private company data in the terms and conditions of the purchase. Had the company utilized a centralized procurement system, the purchase and associated terms and conditions would have gone through a rigorous review to ensure risk is mitigated, and any caveats or concerns would have been flagged and either addressed via new, independent contract or a different supplier may have been selected. Other problems an organization may face include fighting an uphill battle due to lack of existing governance, ambiguous and inconsistent policy application, weak leadership, poor communication, and lack of executive buy-in.

When setting up third-party risk management policies and procedures, figuring out which stakeholders to include can be a daunting task. In addition to procurement, key stakeholders may include representatives from appropriate functional areas and different geographic areas or sites as well as key decision makers and influencers such as subject matter experts and opinion leaders. Each of these stakeholders can be documented or assigned a responsibility or involvement aspect in a responsibility assignment matrix (e.g., a RACI [Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed] matrix), and engagement can be managed and maintained via ongoing engagement plans and other defined departmental/organizational goals. Below are some questions to help guide stakeholder identification:

- Who in the company utilizes third parties or suppliers?

- Who manages the third parties/suppliers’ work?

- Who makes decisions about the third party and supplier work program?

- Who needs to know about the third party and supplier work program?

- Who can benefit from the success of the third party and supplier work program?

- Who can be harmed from the failure of the third party and supplier work program?

- Who can influence the third party and supplier work program culture?

Note that it is crucial for organizations to include third parties as stakeholders. Without including them, an organization will miss key input and feedback when identifying procurement-risk. Other potential sources of strain include lack of consensus, prioritization issues, misidentification of opinion leaders, including third parties in the governance process either too early or too late, varying company cultures between countries/parent companies/affiliates, and poor communication leading to uninformed stakeholders or obsolete policies.

As previously mentioned, lack of executive buy-in hinders implementing third-party risk management policies. If the requirement for supply chain risk management policies does not come from the executives themselves or from a regulatory requirement, other strategies may be useful to gain executive buy-in. It is crucial to speak in terms executives care about and address fundamental questions in the business language. The executive-level audience typically cares most about costs and revenue, so solutions should address how they mitigate potential loss of revenue, for example, revenue lost via decreased business operation or reputational impacts along with relevant likelihood. At a high-level, costs should focus on the cost of ownership before, during, and after implementation. Another consensus-gaining strategy uses a phased approach for implementation that demonstrates small, short-term wins and highlights the near-term qualitative benefits in addition to the broader, quantitative revenue implications.

Obtaining executive buy-in can be challenging for myriad reasons, but most challenges can be tied back to a lack of clarity. Examples include lack of clarity in cost/loss of revenue, in funding source (i.e., CAPEX vs. OPEX), and in non-cyber risks due to inaction, as well as lack of consensus/other priorities. Although supporting a cybersecurity risk mitigation solution with cyber-related metrics is important, presenting potential non-cyber-related damages cannot be overlooked. If a cybersecurity risk mitigation strategy is not implemented, the organization may suffer reputational harm, relationships with third parties may be damaged, contracts may be breached, and/or regulatory bodies may impose fines or other sanctions.

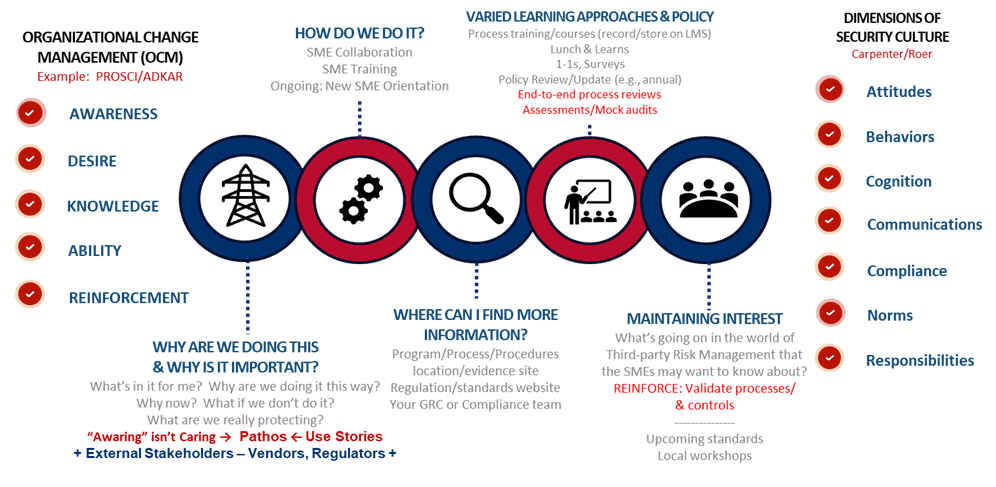

Organizational change management (OCM) is a complicated process with many moving parts as shown in Figure 16. The ADKAR model is an example of an outcome-oriented change management method that aims to reduce resistance to organizational change. Shown on the left side of the figure, ADKAR stands for awareness, desire, knowledge, ability, and reinforcement. In the middle of the image, the five circles expand on each aspect of ADKAR and highlight key points and considerations to help improve acceptance and reduce opposition to new processes and policies in all levels of an organization. Note that OCM models and methodologies are similar, and it is typically most appropriate to leverage the model already in use by the organization.

Figure 16. Organizational Change Management (OCM) model and considerations.

Implementing new processes and policies at an organization is tough as it is and can be further complicated by barriers to change. Some examples include cultural differences, resistance to change, lack of sustainability, difficulties maintaining momentum after implementation, regressing to tactical thinking rather than strategic thinking, among others. Half-baked implementation of new policies and procedures also poses problems, such as missed milestones/deadlines, re-work resulting from not identifying and addressing issues upfront, and other delays in contracts with third parties. Fortunately, OCM methodologies have built-in strategies to help identify, combat, and reduce the barriers to change and downstream impacts from partial implementation. Ultimately, organizations need to establish and build a risk-informed and compliance- and security-focused culture as part of the organizational culture, especially around third-party risk, to prevent major business disruptions. It is important to note that companies do not really have a separate compliance culture—it is really part of organization culture.

To raise concerns and pitch solutions and strategies to mitigate risk, the risks must first be identified via risk assessment. Risk assessments should include employees with varying levels of visibility. The table below outlines the typical levels of visibility and their responsibilities with respect to risk assessments.

Table 3. Levels of Visibility

| Position Title | Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Technical Staff | Involved in risk identification and remediation, including deviations (exceptions) from policies/standards |

| Cyber/Compliance Staff | Translate risk identification into business terms, track mitigation/remediation, review triggers, and manage exceptions |

| CISO/CSO | Sign-off on high-level risks and periodically review residual risks in third-party risk register (exceptions) |

| Business Leaders | Sign-off on risks |

| C-Suite/Board of Directors | Aware of all major risks in the context of enterprise risk/risk register |

Ironically, even assessing risk poses risks of its own. As with any process, the risk assessment process can fail, so it is important to be aware of the potential areas where the process may break down. There could be risk identification issues, risk communication/explanation issues, poor documentation, tracking, and follow-up practices, rigid and strict processes or overly flexible and inconsistent processes, or employees could act on personal motivations and provide inappropriate approvals and signoffs. Thus, it is crucial for organizations to walk through with governance stakeholders and communicate expectations to reduce the ways in which the process could fail.

Additional Resources #

- Miranda, Dana, and Watts, Bob, RACI Chart: Definitions, Uses and Examples for Project Managers – Forbes Advisor, June 2024.

- Athuraliya, Amanda, What is Stakeholder Identification: The Complete Guide with Templates | Creately, April 2024.

- Hiatt, Jeffrey M., ADKAR: A Model for Change in Business, Government and Our Community, Prosci Learning Center Publications, 2006.

- Roer, Kai and Carpenter, Perry, The Security Culture Playbook: An Executive Guide to Reducing Risk and Developing Your Human Defense Layer, Wiley, 2022.