The Emerging Cyber Threats to Industrial Control Systems (ICS)—Supply Chain Cybersecurity #

Webinar #

Recorded on December 14, 2023

Presenter #

- Camilo Gomez, Yokogawa

Presentation

Summary #

In a time defined by rapid technology advancements, the increasing digitalization of critical infrastructure brings new opportunities to modernize and improve the electric sector worldwide. These new opportunities also bring new cybersecurity risks. As organizations embrace digital controls, the supply chain for the electric sector—from new systems within utilities, to cloud services, to integrating third-party operations like distributed energy resource (DER) aggregators—has become an essential consideration in any digitalization project. Electric utilities must recognize indicators of threat, identify potential vulnerabilities, and respond to threats before serious consequences arise. The supply chain is one key place to analyze these risks.

Threat Categorization #

There are several recent high-profile cyberattacks that all utilities should learn from and analyze from their own perspective: the 2016 Ukrainian electric grid attack, the 2020 SolarWinds hack, and the 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware event that led to a gas and diesel fuel panic in the United States are quintessential examples of the potential impact that cyberattacks can have. The attackers in each case had unique motivations, but they engineered each attack in ways that best suited their intended target. The 2020 SolarWinds hack stands out because of the attackers’ abuse of legitimate supply chain channels.

In December 2016, a substation in the Ukrainian electric transmission grid was the target of a cyberattack, resulting in an approximately one-hour blackout in Kyiv, a smaller impact than it could have been. Hackers attacked operational technology (OT) systems and used a malware framework called CRASHOVERRIDE (also known as Industroyer) to target and physically disrupt operations by opening relays to interrupt power flow and digitally wiping equipment to make it unusable among other functions. CRASHOVERRIDE is a modular framework that utilized an initial backdoor to provide attackers with access to the system and then deployed a loader module and payload modules. The modular framework made this malware adaptable to maximize damage and potentially target a wide array of utilities.1

The Colonial Pipeline attack resulted in a six-day halt of the company’s operations in 2021, causing a loss of 100 million gallons of fuel per day to consumers. This led to a gasoline, diesel fuel, and jet fuel shortage panic on the eastern seaboard of the United States. Unlike the Ukrainian grid attack that targeted OT systems, Colonial Pipeline faced a ransomware attack that infected their IT network. The attackers used ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) after accessing the Colonial Pipeline network through a compromised password for a virtual private network (VPN) account of an end-user at the company. Colonial Pipeline chose to shut down operations out of an abundance of caution to ensure the ransomware would not directly impact OT systems.2

In 2020, SolarWinds faced a similar attack on their information technology (IT) systems; however, rather than directly impacting SolarWinds, the attackers inserted malicious code into the Orion framework, SolarWinds’ platform for IT performance monitoring and management, which is used by thousands of organizations. The attackers used a cutting-edge attack method and distributed hidden malware to Orion users through a legitimate, routine software update of Orion that was pushed to client organizations. Unbeknownst to Orion users, upon accepting the compromised software update, the victim organizations inadvertently granted the hackers access to their systems, confidential data, and classified files. In addition to data breaches for multinational companies and government agencies around the world, SolarWinds suffered hundreds of millions of dollars in reputational impact.

Cybercrimes can be analyzed in terms of “who” commits the crimes, “what” is the (potential) impact to the organization, “why” the criminals targeted the victim, and “how” the attack was possible. Five different threat actors who carry out these attacks include: insiders, hacktivists, cyber criminals, nation-states, and terrorists. Although important to be aware of who the attackers are, the “what,” “why,” and “how” behind cybercrime are more important.

Organizations play a crucial role in end-to-end supply chain cybersecurity by taking appropriate actions to respond to and mitigate threats. Whether the attackers exploit people or technology vulnerabilities, ultimately, attackers are only successful if they can gain access to the system, which is something that can be controlled by enacting cybersecurity controls—measures that can reduce the risk of a cybersecurity attack. However, even the most secure organizations are at risk as attack methods are evolving. Supply chain attacks have become more common but remain difficult to detect and protect against.

End-to-End Supply Chain Cybersecurity #

Supply chain cybersecurity is only as strong as its weakest link. To adequately defend against cybercrime, end-to-end supply chain cybersecurity must be prioritized by organizations. End-to-end supply chain cybersecurity places responsibility on all roles—from fabrication to consumption—to tackle threats and reduce vulnerabilities.

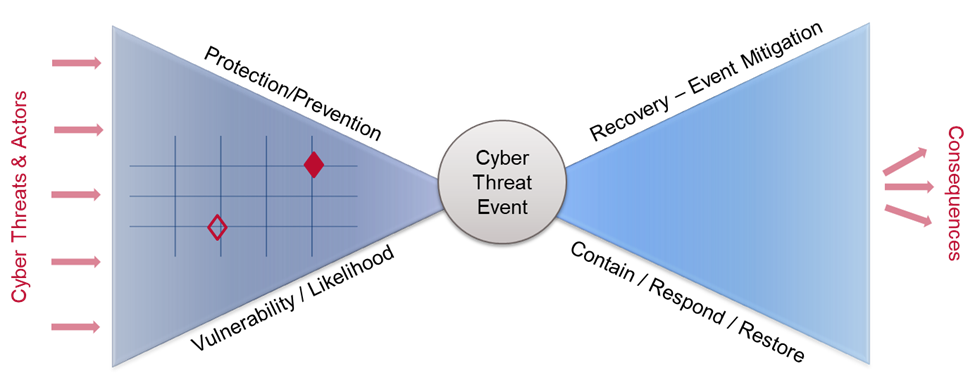

Figure 1. Risk Management Bow Tie

The Risk Management Bow Tie (Figure 1) is a visual, scenario-based method for risk identification, analysis, and management. It provides a framework for analyzing potential malicious cyber threats and actors and possible mitigating actions to minimize any consequences or negative outcomes. The left side of the bow tie represents protective/preventative measures that impede incoming cyber threats and bad actors depicted by inbound red arrows on the left. The right side corresponds to recovery actions in place to reduce consequences. Prevention is based on both the vulnerability and the likelihood of that vulnerability being exploited. Recovery efforts deal with containing the event, responding to the event, and restoring operations to minimize negative outcomes.

On the left side, examples of barriers to cyber threats include security programs, security policies and procedures, infrastructure defense, products with built-in defenses, and threat detection mechanisms. When these mechanisms are not sufficient, recovery measures are enacted to contain and respond to the attack, and to restore the system(s) while mitigating negative consequences. These measures can include triage procedures and altering, response and communication procedures, drill exercises, organizational impact management, and even forensics to identify lessons learned and fortify the system moving forward.3

TSA Pipeline Regulation

One recent example of cybersecurity regulations is the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) Pipeline Security Directive, Pipeline-2021-02 series: Pipeline Cybersecurity Mitigation Actions, Contingency Planning, and Testing. In response to the Colonial Pipeline attack in 2021, TSA mandated that owners and operators of critical liquid and natural gas pipelines establish and implement a Cybersecurity Implementation Plan, develop and maintain a Cybersecurity Incident Response Plan, and establish a Cybersecurity Assessment Program to proactively and continually test implemented cybersecurity measures and identify and correct any vulnerabilities. The scope of the directive is for any IT and OT system or data that, if compromised or exploited, could result in operation disruption, including business services that, if compromised or exploited, could result in operational disruptions (e.g., billing systems).

The requirements in the TSA Pipeline Security Directive align with the Risk Management Bowtie. The Cybersecurity Implementation Plan covers the full bowtie from end to end. The right side constitutes the Cybersecurity Incident Response Plan, and the left side lists the prevention plans and programs that are to be routinely tested for effectiveness in the Cybersecurity Assessment Program.

IT vs. OT Supply Chains #

IT and OT have unique supply chains and unique risks, as shown in Table 1, below. For example, IT systems and devices tend to be refreshed every 2-5 years. OT systems, on the other hand, are not replaced or significantly updated as frequently as IT devices. OT sees technology refreshes typically every 10-15 years, oftentimes even longer, rendering their security and communication protocols obsolete and leaving the systems exposed compared to their more frequently refreshed IT counterparts. These long operational lives place greater importance on quality incident response plans, secure network architecture, and risk-based vulnerability management programs.

Table 1. Unique Challenges in IT and OT Supply Chain Risk Management

| IT | OT | |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Refresh | 2-5 years | 5 years |

| Typical size of capital projects | Millions | Multi-millions to billions |

| Weight of Budget | Capital project: High | Operations: Low |

| Built-in Capability of Legacy | Somewhat capable | Incapable/less capable |

IT and OT supply chains have unique strengths as well, as shown in Table 2, below. Both have their own series of standards that define methods and procedures to protect their assets. IT often follows the ISO/IEC 27000 series that applies to information security management systems (ISMS), and OT follows the ISA/IEC 62443 series that applies to industrial automation and control systems (IACS), with the latter helping bridge the gap between IT and OT. Unlike IT devices, it is common for OT devices to come with cybersecurity, safety, and interoperability certifications due to their long lifecycle and long replacement timeline.

Table 2. Unique Strengths in IT and OT Supply Chain Risk Management

| IT | OT | |

|---|---|---|

| Standards | ISO/IEC 27000 | ISA/IEC 62443 |

| Product Certification | Unpopular | Prevalent |

| Standards Supply Chain Assurance | Product | Both Product and Product Supplier Organization |

OT supply chains further enhance product certifications as it is common for the supplier to also have their own assurances with respect to production standards. Not only are OT products certified, but the companies building and providing the products are certified to have processes in place that align with appropriate standards. As it is less common to provide certifications for IT products, naturally, it is less common to provide assurances that IT product suppliers align with applicable standards.

OT product security certifications frequently follow the ISA/IEC 62443 series of standards. This series addresses end-to-end supply chain cybersecurity by defining standards for each role in the supply chain: product suppliers, service providers, system integrators, and asset owners. Certifications based on the 62443 series holistically assess products and systems to ensure that they are secure by design with built-in security capabilities and free of known vulnerabilities. Other certifications are also available, such as those that ensure support throughout the entire lifecycle of the product, including patches for new vulnerabilities and end-of-life product support.

Vulnerability Intelligence & Management

Vulnerabilities are key to understanding risks. Two vulnerability intelligence and management websites for IT and OT, respectively are CVE.org and CISA.gov. These sites provide vulnerability reporting, vulnerability alerts, and other technical intel for their respective jurisdictions.

The MITRE ATT&CK framework is another valuable vulnerability repository and framework for attack classification where users are able to familiarize themselves with known attack techniques and tactics and learn how to best defend against adversaries.

Additional Resources #

- National Renewable Energy Laboratories (NREL), Resilient Energy Platform

- TSA Pipeline Security Directive 2021-01B (see also the full list of Security Directives)

- ISA Standards

- IEC Standards

- ISASecure Certification: ISASecure - IEC 62443 Conformance Certification

- IECEE CMC Certification

- Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures website

- U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- MITRE ATT&CK

- USEA Webinar on Standards and Best Practices

- USEA Webinar on ISO 27001

-

See ESET: Win32/Industroyer: a new threat for industrial control systems and Dragos, Inc.: CRASHOVERRIDE Analysis of the Threat to Electric Grid Operations for two descriptions of the attack. ↩︎

-

Colonial Pipeline Company, Media Statement Update: Colonial Pipeline System Disruption ↩︎

-

See the section on Cybersecurity Incident Response Plan Development for more information. ↩︎