Leveraging Procurement for Cybersecurity Resilience #

Webinar #

Recorded on April 25, 2024

Presenters #

-

Frank Harrill, SEL, Inc.

Presentation -

Jacob Phillips, MISO

Presentation

Summary #

Procurement in the energy sector plays a pivotal role in strengthening cybersecurity, particularly within transmission system operators (TSOs), distribution system operators (DSOs), and generation entities. By embedding cybersecurity specifications into procurement processes and requirements, utilities can ensure a higher level of security in critical infrastructure systems such as SCADA, energy market applications, advanced metering infrastructure, and billing systems, among others. The integration of cybersecurity into procurement processes not only enhances resilience but also ensures alignment with existing standards to guide and optimize procurements through the lifecycle of operations.

Vendor Cybersecurity Assessment Program #

A vendor cybersecurity assessment program is one effective tactic to embed cybersecurity in the procurement process. Effective vendor cybersecurity assessment programs: (1) start addressing cybersecurity early in the procurement process, (2) leverage global industry standards, (3) use independent third-party assessors, and (4) plan for negotiations with vendors to address areas of weakness.

Early evaluation and management of key vendors is important to ensure that the solution meets the cybersecurity requirements of the organization. Moreover, early evaluation ensures that the cybersecurity requirements have been thought out and planned. Specifications should cover elements such as authentication, authorization, data encryption, and secure coding practices, among others.

By leveraging established global and industry standards, organizations can both better ensure reliability as the standards prove to be effective in industry and ensure that the procuring organization does not have to reinvent the wheel and create a standard to judge a vendor against, thus saving both parties time and money. In the cybersecurity arena, some common global and industry standards include:

-

ISO/IEC 27001: This international standard provides specifications for an ISMS. By adhering to this standard, energy sector entities can manage the security of assets such as financial information, intellectual property, employee details, and information entrusted by third parties.

-

NIST Cybersecurity Framework: Developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, this framework provides a policy framework of computer security guidance for how private sector organizations in the US can assess and improve their ability to prevent, detect, and respond to cyber-attacks. It includes guidelines that can be directly applied to procurement processes to enhance cybersecurity.

-

Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2): Framework designed to help organizations in the critical infrastructure sector assess and enhance their cybersecurity practices by evaluating their maturity across various domains (i.e., risk management, asset management, incident response, etc.).

-

ISA/IEC 62443 Series of Standards: This series of international standards, developed by the International Electrotechnical Commission, focuses specifically on the security of industrial automation and control systems (IACS). It aims to enhance the resilience and security posture of critical systems by providing guidance for risk assessments, system designs, security measure implementation and monitoring, among others.

Organizations can expedite the assessment process by employing independent third parties to assess vendor risk and quality. Many governments, including the United States, develop guidance, frameworks, and regulations that can be used to require compliance in vendors. A risk assessment vendor provides independent industry assessments and ratings of vendor offerings to evaluate their strengths and manage risks. A risk monitoring vendor helps organizations manage cybersecurity by continuously monitoring and assessing product vendors for changes in risk profiles. These monitors may also conduct audits to assure compliance with standards and requirements.

Lastly, effective cybersecurity programs have solid negotiation tactics, both internally and externally. External negotiation tactics aid in times when cybersecurity is not advertised as a strength of a solution despite the solution perhaps meeting or even exceeding all other requirements. In these situations, emphasizing the mutual benefit of strengthened cybersecurity features, offering incentives, or challenging suppliers that disclaim or minimize liability may be successful strategies. Internally, negotiations are needed when a decision-maker chooses to go through with a cheaper solution that meets the bare minimum or even falls short but is granted an exemption. Winning tactics include engaging leadership and gaining support for security as a priority, explaining that upfront costs may be lower, but the potential reliability, financial, and reputational damages later may cause much higher costs, providing examples of failures to appeal to pathos, and being open to compromise and alternatives.

The Procurement Process #

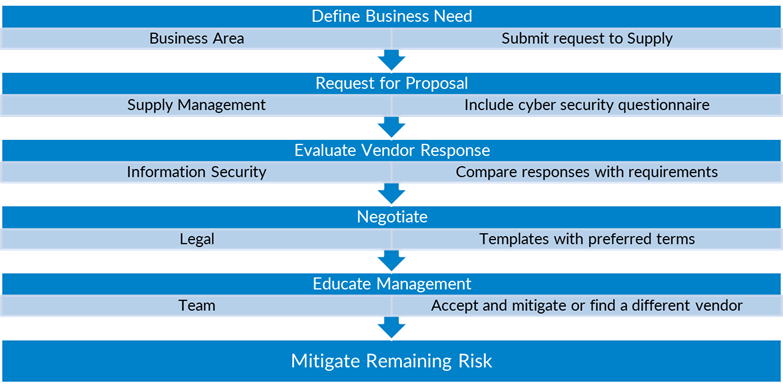

Cybersecurity procurement programs are cross-functional efforts with several different units within an organization. The business area that deploys and uses the product or service should describe the need and their requirements. A supply management group or procurement office should assist with the request for proposal (RFP) process. IT establishes and evaluates the cyber requirements. Legal ensures that the terms and conditions address those requirements adequately. Finally, management provides the final approval, which can only be given if management understands the risks and supports the risk mitigations needed for implementation. Figure 18 below shows the vendor cybersecurity assessment process at MISO at a high-level.

Figure 18. High-level view of the cybersecurity procurement process at MISO.

One of the most important aspects of the procurement process is understanding the business needs that are driving the procurement. Utilities should have a clear understanding of the needs, the network connections that will be necessary to meet those needs, and what information the utility would share with a vendor to meet those needs. The specific cybersecurity capabilities required in the RFP for a product or service will be different whether the vendor’s system will connect to the utility’s sensitive cyber assets or whether it will be isolated from those assets.

It is important to be as surgical as possible about the actual needs and to be accurate upfront. Organizations should establish cybersecurity expectations for vendors early in the procurement process by including those expectations in the RFP. Vendors can then respond appropriately and adjust budgets and plans accordingly. The RFP may contain soft requirements as well, which the solution “should” have, but perhaps are not strictly necessary. The eventual contract will specify the hard requirements, and the utility can plan mitigations for any of the soft requirements that were not fulfilled. Note that if the RFP could contain any sensitive information, then the utility should be looking to trusted suppliers in a private RFP and should implement non-disclosure agreements with those suppliers.

Where and when applicable, organizations can and should use standardized assessments. An example of this is the NATF Questionnaire, a standardized tool developed by the North American Transmission Forum to assess and improve the cybersecurity posture of those involved in the transmission of electricity. Despite its name, the NATF Questionnaire is rooted in cybersecurity best practices overall and aligns with other international standards and thus can be utilized globally. Using a standardized assessment lessens the burden on all parties involved as utilities do not have to develop their own questionnaire, nor do vendors have to respond to a unique assessment for each potential client.

Organizations should identify their critical and non-critical vendors. In general, critical vendors supply products or services without which the utility would have a disruption in operations (i.e., if the product were unavailable or not functioning). The utility should give critical vendors a risk rating, at least qualitatively (e.g., low, moderate, and high), based on the vendor’s capabilities and the controls they have implemented. Standards can be useful to consider the vendor’s capabilities and risk. For example, if a vendor is ISO 27001 certified and agrees to maintain their certification, then that vendor could be considered low risk.

Maintaining vendor relationships and bi-directional communication helps organizations react quickly to cybersecurity incidents. The contract and SLA should define these expectations and requirements, so it is imperative that the contract language is understandable, accessible, and achievable. The Edison Electric Institute (EEI) Model Procurement Contract Language document is a useful reference for contract language but may need to be adapted to other markets or standards.

Contract and Procurement Language #

Contract and procurement language is a form of administrative control, and therefore not effective as a stand-alone control. It is one layer in a multilayered risk control strategy. To be effective, contract language needs to be clear and understandable. Similarly, all parties to the contract need to have the same understanding of the meaning of that language. Standards can be useful to convey this shared meaning. Contract language should also be as simple as possible, but no simpler. Finally, contract language should create flow-down obligations to second- and third-tier suppliers, in part to promote increased cybersecurity awareness and defensive strategies throughout the entire supply chain, especially in today’s world of well-funded adversary groups.

The contract language contains only the hard requirements which the vendor must adhere to. Therefore, it is important for utilities to ensure that they are only requiring terms that they actually need, rather than wasting time and resources on extraneous things. Note that these requirements will likely change from one system to another, so including a “standard” list of technical controls in the contract language could cause unintended consequences. A list of information technology controls might not be applicable on an internal network within the OT environment. For example, if contract terms require that every device that must support Azure AD/Entra ID, then the utility could end up requiring such functionality in something like a PLC that does not really need it.

Similarly, if contract language is too specific, the procuring utility might not have the flexibility to meet the particular needs of the project. This is especially true if the contract will be in place for years, while technology could change or threats can evolve. Instead, utilities can make it clear that requirements can be developed through the life of the contract.

Trust But Verify #

Building trusted relationships with suppliers can be mutually beneficial for both the procuring utility and the suppliers. Procurement is more than driving to the lowest possible price and checking off boxes—it is a true business partnership that requires collaboration and communication to better meet the needs of both parties. Utilities should verify that suppliers deliver products and services as expected. Moreover, utilities should establish redundancy whenever possible. Trusting but verifying may involve on-site visits (if possible) to ensure that the supplier is delivering what was promised, or it may involve independent, accredited third parties to audit and certify that the necessary controls are in place, such as those required to meet ISO 27001 and IEC 62443. While certification to these international standards is widely respected, there can be a misunderstanding about the scope of the certification. Depending on the standard, suppliers may be certified only for specific products/product lines or only at certain locations. Thus, it is imperative that procuring organizations ask for and review the statement of applicability and the scope that is associated with each certification.

For suppliers that are not certified to one of these international standards, the NATF questionnaire can help ascertain the supplier’s cybersecurity competence. In any case, utilities should verify that the supplier has business continuity and incident response plans in place, at a minimum. That said, disclosure of sensitive information can create undue risk for the supplier and utility, which may have concerns about data leaks and additional security for third party information respectively. Visual inspection of this information or reliance on independently audited third-party certifications may suffice.

Finally, utilities may also conduct a surface-level assessment of their suppliers by reviewing the security practices associated with the supplier’s internet presence. Two notable tools to use are:

- https://securityscorecard.com/security-rating/[insert domain name of supplier]

- https://webscan.upguard.com/

Note that these sites are not foolproof and can return false positives, but they can still be a valuable preliminary assessment of potential suppliers and give the procuring organization a rough idea of if or how they want to proceed in subsequent conversations.

Evaluating suppliers is never a one-time action; suppliers must be continually assessed to confirm that expectations are being met.

Additional Resources #

- Security Scorecard: https://securityscorecard.com/security-rating/[insert domain name of supplier]

- UpGuard

- EEI, Model Procurement Contract Language Addressing Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk, Version 3.0, October 2022