Standards on Third-Party Risk Management and Cyber Risk Assessment Methodologies #

Webinar #

Recorded on January 11, 2024

Presenters #

- Frances Cleveland, Xanthus Consulting International

- Gigi Pugni, START 4.0 Competence Center

Presentation

Summary #

There are several internationally accepted standards and guidelines that can help address third-party risk management and cyber risk assessment methodologies and mature their risk-management practices.

Cybersecurity is not only a technology issue; it is also an organizational concern that requires appropriate policies and procedures in addition to security technologies. Risk is inherent in operations, so a risk assessment is essential to determine the appropriate mix of policies, procedures, and technologies. One critical aspect of any cybersecurity risk assessment is supply-chain cybersecurity.

Unique Qualities of Supply Chain Cybersecurity Standards #

Most cybersecurity standards focus on the actions a single organization should take to secure their own people, systems, and operations. Typically, an organization can implement top-down control over their own internal cyber risk management to achieve desired results. Supply chain security risks, on the other hand, involve multiple organizations, which makes these issues complex in relation to other security issues.

The supply chain is often thought of as the procurement of products from other organizations, but it also includes services like access to information such as markets and cloud services, which therefore relies on external communication networks. As DER become more common, utilities must incorporate equipment from other organizations into their operations as well. These interactions with third party entities add to the complexity.

Supply Chain Risks and Vulnerabilities #

Supply chain cybersecurity risks are unique compared to many of the usual cybersecurity considerations. Some examples of supply chain risks can include but are not limited to:

- Utility interfaces to third-party products which contain malicious code

- Supplier provides lower quality or counterfeit products due to their supply chain problems

- Utility develops software using code from compromised sources

- Utility purchases energy management products from vendors who have deliberately or accidentally incorporated malicious code into their systems

Due to the complexity of the supply chain, there could be numerous points of failure. In many cases, the vulnerability may stem from the utility’s failure to do something, such as not having a comprehensive security policy for OT systems, not having a procurement policy that considers cybersecurity, not checking the vendors’ supply chain policies, not testing products from vendors, not having multiple vendors for essential products and services, and not enforcing supply chain security requirements on vendors. For example, when utilities bring on DER resources through a third-party aggregator, a contractual agreement should specify requirements, including roles and responsibilities, for both the utility and the third party.

Key Actions to Address Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

Risk Assessments — These assessments are essential to understand the threats, vulnerabilities, and potential impacts. Formal assessment processes systematically consider each area while accounting for the scope of the assessment: the product, system, or organization under assessment.

Power System Monitoring — OT security is sometimes referred to as cybersecurity plus physics. The underlying physical processes of delivering electricity can be an important source of information for identifying anomalies in digital controls, not just within your own organization, but also the interconnecting systems.

Contractual Agreements — Contracts specify requirements for suppliers to hold them accountable for their own cybersecurity risk management and may set minimum expectations around the suppliers’ capabilities for protection, detection, response, and recovery, as well as specifics for roles and responsibilities during and after an incident.

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) — External suppliers frequently need some access to the utility’s systems. RBAC is a best practice for implementing strong access control and limiting permissions.

Use of Gateways — Placing gateways in front of and/or between critical systems (e.g., between a utility’s supervisory control and data acquisition [SCADA] and an aggregator’s DER management system [DERMS]) enables several beneficial controls like access control, data validation, protocol security and agreements.

Standards on Third-Party Risk Management #

NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 #

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 is the latest version of one of the most popular international frameworks used to guide organizations building a cybersecurity program. The NIST Framework is an excellent starting point for considering enterprise C-SCRM, which is included as a “Category” in the “Govern” function of the Framework. The Govern function is new in version 2.0 of the Framework, but it matches the lived experience of many organizations: starting with Governance issues, and developing strategies for addressing cybersecurity, including C-SCRM, is an essential step for both large and small companies.

The new version of the NIST Framework includes new subcategories within the C-SCRM category. Previous subcategories promoting a C-SCRM risk management plan, integration of C-SCRM into enterprise risk management, understand and management of risks associated with suppliers, and including suppliers in incident management plans remain in the new version. In addition, organizations are now encouraged to know their suppliers and prioritize them in terms of their criticality, to perform due diligence before entering formal relationships, to integrate C-SCRM practices in overall risk management programs, and to extend risk management plans through and beyond the conclusion of the relationship with the supplier. Integrating C-SCRM practices into overall risk management programs means not only that organizations must be collecting appropriate information from their suppliers,1 but also that organizations must set clear expectations on what suppliers must do to support the organization’s cybersecurity.

NIST Special Publication 800-161r1, Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Systems and Organizations #

The NIST Special Publication 800-161r1, “Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Systems and Organizations”, provides a comprehensive look at C-SCRM issues. This document highlights the reduced visibility, understanding, and control with each step along a supply chain from the acquiring enterprise to their first-tier suppliers, to the second tier, and so on. NIST SP 800-161r1 highlights the activities needed to manage the cybersecurity risk associated with external parties into five categories, which enable an organization to:

- Determine cybersecurity requirements for suppliers

- Implement requirements through formal agreements

- Communicate to suppliers how these requirements will be verified and validated

- Verify that cybersecurity requirements are met through a variety of assessment methodologies

- Continuously maintain and improve the entire process proactively

Translating Requirements Standards to Technical Implementation #

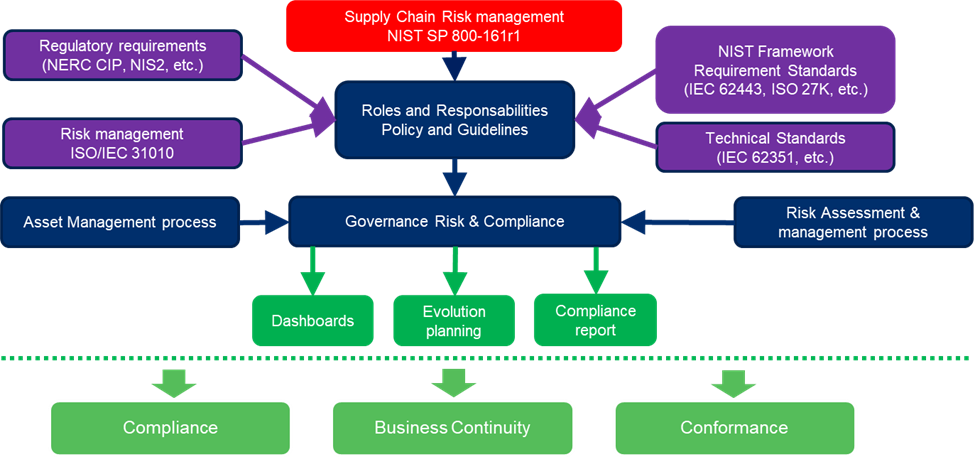

Requirement standards like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, ISO/IEC 62443, and ISO 27001 are broader than just C-SCRM and provide a good starting point for developing a security program. Technical standards like ISO/IEC 62351 and guidance standards like ISO 31000 on risk assessments also provide supporting details for a cybersecurity program. These standards and the NIST SP 800-161r1 standard on C-SCRM provide requirements that an organization can translate into policies and guidelines that reflect the unique reality within the organization, for example, defining roles and responsibilities that align with the personnel and capabilities within the organization (see Figure 2, below). These “global policies” establish the rules of the game for the organization to follow and apply to its unique risks and the underlying assets.

Figure 2. Relationship of various standards to support organizational cybersecurity risk management.

The global policies should be understood and supported by top management and address both internal and external parties. Policies, however, do not specify implementation details and must be translated into the specific requirements for implementation in each context. For example, to carry out a policy that requires RBAC, the organization may need to develop a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) system. Deploying a technical system like PKI may require another level of specificity supported by standards, e.g., one of the communication protocols security profiles in the IEC 62351 family of standards.

The details of the global policies, the contextual requirements, and the technical specifications will be important not only for the internal controls, but also for external parties to deliver solutions that fit the organization. Moreover, requirements from international standards like ISA/IEC 62443 and IEC 62351 will be easier for suppliers to understand and implement than an idiosyncratic internal standard would be. Responsibility for each requirement or control should be clearly assigned to specific actors of the supply chain (e.g., client, integrator, manufacturer, service provider).

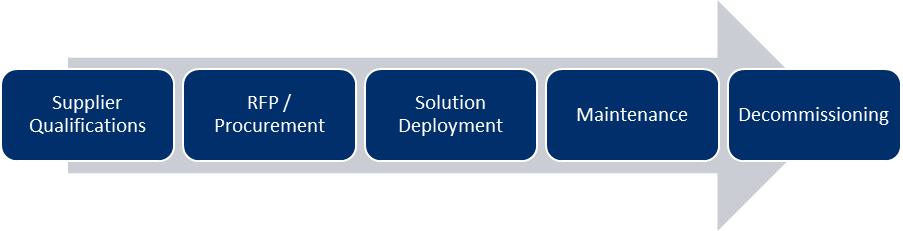

C-SCRM Lifecycle #

The C-SCRM lifecycle is a 5-step process involving each stage of the supply chain, as shown in Figure 3. The first stage begins with understanding and assuring that manufacturers and providers have the right qualifications, including appropriate cybersecurity certifications and competencies. Suppliers must understand that they should be compliant to expected standards such as ISA/IEC 62443 and the ISO 27000 series.

Figure 3. C-SCRM Lifecycle.

The second stage is developing the request for proposal (RFP). A risk assessment should be conducted on the product or service’s intended use cases. A utility should consider adding a clause to all contracts with a supplier allowing for periodic audits of technical standard compliance. The utility should ensure that there are significant event notifications and vulnerability alerts when adding new products to the system. Additionally, utilities should ensure that there are lifecycle clauses in contracts, so that suppliers can patch, maintain, and decommission devices and products when necessary.

Following the purchase of a product or service, the enterprise can develop and deploy the solution. The enterprise should design these solutions with security in mind from the beginning and throughout the entire development cycle. The security of these solutions should be standards based (IEC 62531, etc.).

As the solution is deployed into systems and actively in use, a maintenance plan must be developed. Business continuity processes and regular testing can occur on the system to ensure proper functionality. Patching and maintenance plans can be developed to ensure that there are no known vulnerabilities in the solution. Regular audits can be scheduled to ensure that proper maintenance is followed. The utility can develop a Cybersecurity Incident Response Team (CSIRT) to address any identified issues.2

The decommissioning phase falls at the end of the lifecycle, where the solution or product is phased out of use. Company sensitive data must be secured and disposed of properly according to regulatory and compliance requirements.

ISO 31000 – Risk Management Applied to Supply Chains #

The ISO 31000 standard on Risk Management starts with identifying the scope, context, and criteria for the risk management activities, similar to other standards discussed above. Without these high-level considerations captured in policies, it would be impossible to manage the vendor relationships. As the organization’s business processes and risks change, the scope, context, and criteria should be re-evaluated to ensure continuous improvement.

The second step in the ISO 31000 risk management process is the risk assessment. There are many methods to follow, particularly NIST SP 800-161r1 discussed above. Organizations must adapt whatever method they follow to their own operations. Questionnaires and interviews are solid sources of performing a risk assessment, but it is also important to gather statistical information on the success of supplier quality.

This standard also highlights communications, not only with internal stakeholders, but also with vendors, customers, and authorities. Finally, the steps above feed into the risk treatment, which accounts for all the previous considerations.

Tailoring Standards to the Organization #

Starting with governance is essential because it defines the rules of the game in a way that makes sense for your organization. For example, organizations in the electric sector may face regulatory requirements that make certain supply chain related actions difficult, such as notification timelines for vulnerabilities. A long and intricate supply chain will make the notification process difficult, increasing the chance of falling out of compliance with a regulation with strict notification timing requirements. A second example is the OT assets that electric utilities rely on. OT assets have much longer lifecycles than IT assets, and they tend to be more distributed, which may mean solutions meant for IT will not be supported by OT assets, so policies should be tailored with these considerations in mind.

Additional Resources #

- NIST SP 800-161r1, Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Systems and Organizations

- NIST Cybersecurity Framework v2.0

- European Energy Information Sharing & Analysis Centre (EE-ISAC)

- ISO/IEC 27001 – Information Security Management System

- ISA/IEC 62443 Standards – Security of Industrial Automation and Control Systems

- IEC 62531 – Cyber Security Series for the Smart Grid

- ISO 31000 Risk management

-

See the Procurement section for more information. ↩︎

-

See, for example, discussion of Implementation Phase and Post Implementation Phase & Offboarding in the section Coordinating Cybersecurity Risk Management with Hardware/Software Vendors ↩︎